The Multiple Sclerosis and Diet Saga

The Multiple Sclerosis and Diet Saga

The End and a New Beginning

People often ask me: Why are you spending $750,000 from the McDougall Research and Education Foundation to study the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) with your diet? Why not carry out research on a more common problem, like obesity, heart disease, or diabetes?

Most people can’t even pronounce ‘multiple sclerosis’—so they just call it MS. It is likely you don’t personally know anyone with this disease; after all, only 350,000 people in the United States and one million worldwide have it. You may have heard of it because a few famous people have made their disease public, like: lead anchor on Fox News Channel Neil Cavuto, former Mouseketeer Annette Funicello, singer Lena Horne, comedian Richard Pryor, and talk show host Montel Williams. Only 10,000 new cases are diagnosed in the United States annually, compared to half a million new major cancers and 1.25 million fresh heart attacks. So why pick MS?

For me, stopping multiple sclerosis with the cost-free, side-effect-free McDougall Diet is equivalent to throwing the biggest rock I can find at the biggest picture window in town. The shatter will be heard around the world. If diet can effectively treat a disease as mysterious and deadly as MS, then diet has to be a medical miracle—and could easily be capable of bringing to an end diseases long accepted as due to diet, like type-2 diabetes, heart disease, and common cancers. A simple cure for MS would startle even the most unconscious medical doctors into awakening. Plus, I owe this study, and much more, to my mentor Roy Swank, MD for his friendship, guidance, and pioneering work.

The first part of the saga of the treatment of MS with a low-fat diet ended less than 2 months ago on November 16, 2008 with the death of Dr. Swank at age 99. The saga begins anew with the approval of a randomized, controlled study of diet and multiple sclerosis by the Oregon Health & Science University Research Integrity Office on January 15, 2009. This landmark approval only happened after years of hard work by many of us. You have made important financial contributions to the McDougall Research and Education Foundation (a nonprofit, 501(c)(3) corporation) over the past 5 years. Raising sufficient funds allowed me to make my first contact with the Neurology Department of the medical school at the University of Oregon on September 15, 2007. After nearly a year and a half of working with a few of the top people at the medical school, especially Vijayshree Yadav, MD, we are ready to begin.

The Disease

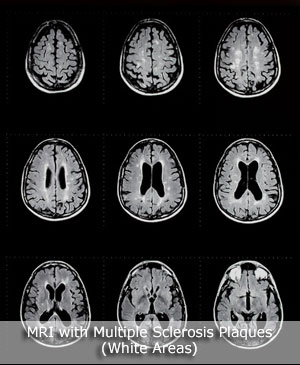

MS is an autoimmune disease—one in which the body attacks itself—in this case the immune system attacks the tissues of the brain and spinal cord (more specifically, the myelin sheaths surrounding the nerve fibers). Isolated areas become intensely inflamed with sores. In time, the damaged tissues heal, but often leave thickened, fibrous scars (scleroses), which doctors commonly call ‘plaques.’

The diagnosis is most often made between the ages of 15 and 50, with women three times more likely than men to develop MS. The initial and subsequent attacks can last one to three months. During an attack the patient experiences visual disturbances, weakness, clumsiness, spasticity, fatigue, numbness, tingling, problems with thinking, slurred speech, pain, depression, difficulty swallowing, bladder and bowel incontinence, and/or sexual difficulties. Rather than on any fancy tests, the diagnosis is based upon a patient’s history and the physician’s examination. Apparently random damage to the nervous system—as if an inexpert marksman shot bullets at the brain and spine—is the hallmark of MS. Sophisticated technologies, like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and associated areas, can help with the diagnosis and show the size and location of active lesions and plaques.

Patients are most often classified as having one of two forms of MS: ‘relapsing-remitting’ characterized by intermittent attacks; and ‘primary-progressive’ with a steady, but usually slow, decline. Actually these ‘doctor-invented’ subtypes are just different stages of the same disease. Usually (80% of the time) at the beginning of the disease the attacks seem to come and go, but in time most cases become progressive. Those patients who appear to start with a progressive decline (20%) have simply skipped the more common initial appearance of relapse and remittance. These artificial categories can be counterproductive, leading to false reassurance and unwarranted despair, and do not predict the prognosis or improve the chances of an effective treatment for the patient. Even with the use of the most modern medications, costing $20,000 a year, the future prospect is dismal with half of those people afflicted with MS unable to walk unassisted, bedridden, wheelchair bound, or dead within 10 years of diagnosis. The absolute advantage for slowing disability with the use of the most popular medications (interferon beta) is clinically small (8%), and the costs and side effects are huge. The lack of substantial benefits from current drug therapies is one more important reason I picked MS to study.

The Cause

Worldwide, multiple sclerosis is common in Canada, the United States and northern Europe; and rare in Africa, Japan, and other Asian countries. This difference most likely reflects the populations’ different diets (animal- vs. starch-based). Scientists have found a very strong positive correlation when consumption of cow’s milk is compared with the incidence of MS worldwide. One theory proposes that cow’s milk consumed in infancy lays the foundation for injuries to the nervous system that appear later in life. Cow’s milk contains one fifth as much of an essential fat, called linoleic acid, as does human mother’s milk. Children raised on a linoleic acid-deficient, high-animal fat diet—as are most kids in our modern affluent society—are quite possibly starting life out with a damaged nervous system, susceptible to insults and injuries in later life. The possible sources of injury that can precipitate the attacks of multiple sclerosis in mid-life are suspected to be viruses, allergic reactions, and/or disturbances of the flow of blood to the brain caused by a high-fat diet.

The most commonly held theory these days proposes an autoimmune basis for this disease. MS has much in common with autoimmune type-1 diabetes mellitus, including nearly-identical ethnic and geographic distribution, and genetic factors. The damage to the nervous system may occur through a process known as molecular mimicry. In susceptible people, cow’s milk protein may enter the bloodstream from the intestine. The body recognizes this as a foreign protein, like a virus or bacteria, and makes antibodies against it. Unfortunately, these antibodies are not specific only to the cow’s milk protein; they find similar proteins in the nervous system (the myelin). The antibodies attach to these nerve tissues and destroy them. In the case of diabetes, the antibodies looking for cow’s milk protein attack the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas.

Roy Swank, MD—My Mentor

There are many people whose shoulders I stand on and the founder of the Swank Diet for MS was one of my most important teachers. In 1977, I was on my neurology rotation for my Internal Medicine Residency at the University of Hawaii. I was given an assignment to present a conference to fellow doctors on any subject of my choosing. My trip to the library that afternoon led me to the discovery of Dr. Swank’s work.

Swank devised his low-fat diet and began treating MS patients at Montreal Neurological Institute in 1948. He recommended not more than 40 to 50 grams of total fat (compared to 150 to 175 grams in the American/Canadian diet) and 0 to 15 grams of saturated fat (compared to 140 to 165 grams). There was no limit on the amount of carbohydrate from starches, vegetables, and fruits. Polyunsaturated fats were increased a little (from 15 to 25 to 20 to 35 grams). Dr. Swank believed MS patients were unique in that they had a heightened sensitivity to saturated fats.

His research soon showed that with adherence to the diet relapses decreased by about 70 percent in the first year of treatment (from 1 relapse per year to 0.2 per year). Then after the first year there were continued improvements (about 5% fewer relapses per year for the next 2 years). For the first 16 years of treatment with a low-fat diet the rate of exacerbation (new attacks and/or decline) was decreased by 95%. (Compare this to the dismal results of drug therapy, mentioned above, where half of patients are in serious trouble within 10 years.)

For outstanding results, patients have to follow the Swank Diet strictly because even small amounts of fat make a huge difference. In the study he published in the medical journal, the Lancet, in 1990, Dr. Swank found that a difference of eight grams of saturated fat intake daily resulted in a threefold increased chance of dying from multiple sclerosis. (That means daily consumption of as little as one ounce of pork sausage at 10 grams, one medium cooked hamburger at 14 grams, an additional three ounces of porterhouse steak, or two ounces of cheddar cheese at 12 grams, significantly increases the risk of dying.)

Early cases are expected to do especially well on the diet. As the years with the disease accumulate then the response to diet is expected to be less dramatic, but there are exceptions with some advanced cases responding very well. If a person begins the program with limited disability and follows the Swank Diet carefully he or she has less than a 5% chance of dying from MS over the next 34 years—those who do not follow the diet have an 80% chance of dying. If patients go off of the diet for a month or so they will get into trouble. Dr. Swank states, ‘Our figures show that at least 95% of people with MS that follow a low-fat diet show no progression of disease.’ However, with normal aging there is deterioration of the nervous system even when the MS disease is not active.

According to Dr. Swank, about one in 500 people will have a downhill course even when they follow the diet strictly. About 50% of his patients followed the Swank Diet really well, whereas 25% were a little over on fat intake and another 25% were a lot over. Dr. Swank said to me, ‘I tell people that they have to have persistence and a real desire to get well or be well or there is no point on going on this (the diet). If they are not devoted to taking care of their health then they are going to have trouble; and finally, I tell them to be optimistic, it’s very helpful.’

You can listen to a free podcast of a radio interview I did with Roy Swank in 1995.

The Swank vs. The McDougall Diet

The Swank Diet focuses on drastically reducing saturated fats, which are abundant in red meats and high-fat dairy products. Included in his diet are low-fat dairy foods (skim milk, fat-free cheese, fat-free ice cream, etc.), egg whites, skinned white-meat chicken, white fish and shellfish. Meats with significant amounts of saturated fats are allowed only in very small amounts.

Dr. Swank also included additional vegetable and fish oils in his diet. He explained to me that he did this mostly because he believed that this addition would make the diet easier to follow. He found that when people ate more polyunsaturated oil they then ate less saturated fat. He also felt the patients’ skin was better with a little oil added, and that they felt more energetic. As far as the fundamental course of the disease was concerned, he did not believe adding the vegetable or fish oil made any real difference—as he explains, ‘It just makes it easier to follow the diet.’ Dr. Swank approved of The McDougall Diet for the treatment of MS, and said so many times. The McDougall diet is very low in saturated fats. As an internist concerned about all aspects of a patient’s health I prescribe a stricter and, I believe, a much more effective (and tastier) diet. Even low-fat dairy and meat products are a health hazard causing infectious diseases, allergic reactions, as well as delivering high loads of animal protein (causing osteoporosis, kidney stones, liver, and kidney damage) and environmental chemicals. These animal foods are completely deficient in dietary fiber and low in carbohydrate. Although lower in fat and cholesterol, low-fat meats and dairy products can still contain substantial amounts of both harmful ingredients.

The dairy proteins are of particular concern to me because they are the leading cause of autoimmune diseases. As I mentioned above, MS is an autoimmune disease and has substantial similarities to another autoimmune disease, type-1 diabetes, which an abundance of scientific research says is caused by dairy protein.

I do not add ‘free’ vegetable or fish oils because they are, at best, medicines, and at worst, toxins. At the very least they can produce weight gain—the fat you eat is the fat you wear. These polyunsaturated oils ‘thin the blood,’ contributing to the risk of bleeding, say, following an auto accident. These fats also suppress our immune system—we need our immune system functioning at full capacity to fight off infections and cancer.

Why Is Diet-therapy for MS Virtually Unknown?

Dr. Swank told me, ‘One problem is culture: we are a meat and potatoes society. Most importantly there is an economic problem, there is really not much money in a diet. Nutrition has not been taught in medical school for many years now.’

More than 20 years ago, during one of my many visits with Dr. Swank at his Oregon medical school office, I asked him, ‘Why is it that when MS patients ask their doctors about changing their diet, they are told this is quackery? And why does the MS Society offer a similar message? You have published in the world’s most respected scientific journals that a simple, cost-free diet can stop this disease. Yet, they summarily dismiss you and your work.’

He leaned back in his chair, took a moment for thought, and then explained, ‘You know, most people in this country expect to be cured by a pill, and to have a cure that is almost instantaneous. With the low-fat diet, the people actually have to work to get better, and have to cure themselves. And as far as the MS Society is concerned, John, they don’t mention it because they didn’t discover it. It wasn’t their research dollars that found this treatment. So they’re not going to tell anybody. I discovered it in my small office here, in the basement of the University of Oregon Medical School.’

So it is not just money that keeps people from highly effective dietary cures; egos are also involved—the well-known business doctrine, Not Invented Here, is working to keep you and your family sick. Self-centered people think, ‘If I didn’t invent it then there is no real reason for me to promote it, especially when there is no fame or fortune in it for me.’

Learn more by reading articles and Star McDougallers found on my web site.

Would you like to help MS patients?

We can change medical practice. Donations are almost painless when made by PayPal to The McDougall Research & Education Foundation A Tax Deductible Corporation

References:

1) Confavreux C, Vukusic S. Natural history of multiple sclerosis: a unifying concept. Brain. 2006 Mar;129(Pt 3):606-16.

2) Andersson PB, Waubant E, Gee L, Goodkin DE. Multiple sclerosis that is progressive from the time of onset: clinical characteristics and progression of disability. Arch Neurol. 1999 Sep;56(9):1138-42.

3) Myhr KM, Riise T, Vedeler C, Nortvedt MW, Grønning R, Midgard R, Nyland HI. Disability and prognosis in multiple sclerosis: demographic and clinical variables important for the ability to walk and awarding of disability pension. Mult Scler.2001 Feb;7(1):59-65.

4) Kremenchutzky M, Cottrell D, Rice G, Hader W, Baskerville J, Koopman W, Ebers GC. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. 7. Progressive-relapsing and relapsing-progressive multiple sclerosis: a re-evaluation. Brain. 1999 Oct;122 (Pt 10):1941-50.

5) Bergamaschi R, Montomoli C, Candeloro E, Fratti C, Citterio A, Cosi V. Disability and mortality in a cohort of multiple sclerosis patients: a reappraisal. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(1):15-8.

6) Cottrell DA, Kremenchutzky M, Rice GP, Koopman WJ, Hader W, Baskerville J, Ebers GC. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: a geographically based study. 5. The clinical features and natural history of primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1999 Apr;122 (Pt 4):625-39.

7) Pittock SJ. Interferon beta in multiple sclerosis: how much BENEFIT? Lancet. 2007 Aug 4;370(9585):363-4.

8) Kappos L, Freedman MS, Polman CH, Edan G, Hartung HP, Miller DH, Montalbán X, Barkhof F, Radé EW, Bauer L, Dahms S, Lanius V, Pohl C, Sandbrink R; BENEFIT Study Group.Effect of early versus delayed interferon beta-1b treatment on disability after a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis: a 3-year follow-up analysis of the BENEFIT study. Lancet. 2007 Aug 4;370(9585):389-97.

9) Butcher J. The distribution of multiple sclerosis in relation to the dairy industry and milk consumption. N Z Med J. 1976 Jun 23;83(566):427-30.

10) Malosse D. Correlation between milk and dairy product consumption and multiple sclerosis prevalence: a worldwide study. Neuroepidemiology. 1992;11(4-6):304-12.

11) Agranoff BW. Diet and the geographical distribution of multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1974 Nov 2;2(7888):1061-6.

12) Winer S. T cells of multiple sclerosis patients target a common environmental peptide that causes encephalitis in mice. J Immunol. 2001 Apr 1;166(7):4751-6.

13) Lauer K. Diet and multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1997 Aug;49(2 Suppl 2):S55-61.

14) Swank R. Effect of low saturated fat diet in early and late cases of multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1990 Jul 7;336(8706):37-9.

15) Swank R. Multiple sclerosis: fat-oil relationship. Nutrition. 1991 Sep-Oct;7(5):368-76.

16) Swank R. Multiple sclerosis: the lipid relationship. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988 Dec;48(6):1387-93.

17) Swank R. Multiple sclerosis: twenty years on low fat diet. Arch Neurol. 1970, Nov;23(5):460-74.

18) Guggenmos J, Schubart AS, Ogg S, Andersson M, Olsson T, Mather IH, Linington C. Antibody cross-reactivity between myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein and the milk protein butyrophilin in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2004 Jan 1; 172(1): 661-8.

19) The August 2007 McDougall Newsletter article: When Friends Ask: Why Do You Avoid Adding Vegetable Oils?

Recommended Articles

The Truth About Oxalates & Kidney Stones

Giving Thanks