McDougall Moments: Where do you get your Protein?

If you don’t know where you get your protein while following a plant-food-based diet, you’re in good company. The Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association, scientists from the Human Nutrition Research Center and Medical School at Tufts University, and registered dietitians, research nutritionists and physicians of Northwestern University, and the Harvard School of Public Health are just a few examples of “experts” you look to for advice who have the protein story wrong.1-4 Consequences of their shortfall are as grave as a lifetime of sickness and obesity, and premature death, for innocent people. These professionals must be held accountable.

Although plant proteins form a large part of the human diet, most are deficient in 1 or more essential amino acids and are therefore regarded as incomplete proteins. (American Heart Association)

Plant protein sources, although good for certain essential amino acids, do not always offer all nine essential amino acids in a single given food. For example, legumes lack methionine, while grains lack lysine. (Tufts Human Nutrition Research Center)

Single plant protein foods usually are lower in protein quality than most animal proteins because they lack significant amounts of various essential amino acids. (Tufts University Medical School)

Other protein sources lack one or more amino acids that the body can’t make from scratch or create by modifying another amino acid. Called incomplete proteins, these usually come from fruits, vegetables, grains, and nuts. (Harvard School of Public Health)

Plant sources of protein (grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds) generally do not contain sufficient amounts of one or more of the essential amino acids. Thus protein synthesis can occur only to the extent that the limiting amino acids are available. (Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University)

Don’t think it matters little if our public policy makers and educators remain ignorant about our nutritional needs. Misinformation leads to disastrous outcomes. People have serious health problems like heart disease, type-2 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and inflammatory arthritis that can be easily resolved by a diet based solely on plant foods. However, advice to make this dietary change may be withheld from you or a family member because of the erroneous fear that such a diet will result in a greater catastrophe, like a nutritional collapse from protein deficiency.

Consider this scenario: Your loving husband of 35 years has a massive heart attack. He recovers and both of you pledge you will do anything‚ even eat cardboard‚ in order to avoid a repeat experience. On your first follow-up visit you tell your doctor that your family is going to follow a low-fat, vegan diet (all plant foods) from here on out. Your doctor says, “You can’t do that; you will become protein deficient‚ plant foods are missing essential amino acids‚ you must eat meat and other high quality animal foods.” Even though you vigorously explain meat, dairy, and eggs are the reasons you almost lost your husband, your doctor insists that you would be foolish to embark on such a course and defends that position with the writings of the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association.

In an October 2001 research paper published in the Heart Association’s journal, Circulation, the Healthcare Professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism wrote, “Although plant proteins form a large part of the human diet, most are deficient in 1 or more essential amino acids and are therefore regarded as incomplete proteins.”1 My letter to the editor correcting this often quoted, but incorrect information, about the adequacy of amino acids found in plants was published in the June 2002 issue of Circulation.5 Another letter from me in the November 2002 issue of Circulation demanded a correction.6 But, the head of the nutrition committee, Barbara Howard, PhD, would not admit she was wrong and used research from the world’s leading expert on protein, Professor Joe Millward, to defend her position.6

Joe Millward, PhD, Professor of Human Nutrition, University of Surrey (England), reviewed the published letters of disagreement between the American Heart Association (AHA) and myself, and wrote the following to me on July 10,2003, “I thought I had made my position quite clear in my published papers. In an article I wrote for Encyclopedia of Nutrition (Millward DJ. 1998 Protein requirements. Encyclopedia of Nutrition. Academic Press pp 1661-1668) I said ‘Contrary to general opinion, the distinction between dietary protein sources in terms of the nutritional superiority of animal over plant proteins is much more difficult to demonstrate and less relevant in human nutrition.’ This is quite distinct from the AHA position which in my view is wrong.”7

I informed the American Heart Association about Dr. Millward’s position, but so far they have chosen to remain silent‚ and annually, 1.25 million people in the USA alone suffer with heart attacks‚ an often fatal condition entirely preventable by following a low-fat diet based solely on plant foods‚ all of which contain all of the essential amino acids in ideal amounts for humans.

Proteins are made from chains of 20 different amino acids that connect together in varying sequences‚ similar to how all the words in a dictionary are made from the same 26 letters. Plants (and microorganisms) can synthesize all of the individual amino acids that are used to build proteins, but animals cannot. There are 8 amino acids that people cannot make and thus, these must be obtained from our diets‚ they are referred to as “essential.”

After we eat our foods, stomach acids and intestinal enzymes digest the proteins into individual amino acids. These components are then absorbed through the intestinal walls into the bloodstream. After entering the body’s cells, these amino acids are reassembled into proteins. Proteins function as structural materials which build the scaffoldings that maintain cell shapes, enzymes which catalyze biochemical reactions, and hormones which signal messages between cells‚ to name only a few of their vital roles.

Since plants are made up of structurally sound cells with enzymes and hormones, they are by nature rich sources of proteins. In fact, so rich are plants that they can meet the protein needs of the earth’s largest animals: elephants, hippopotamuses, giraffes, and cows. You would be correct to deduce that the protein needs of relatively small humans can easily be met by plants.

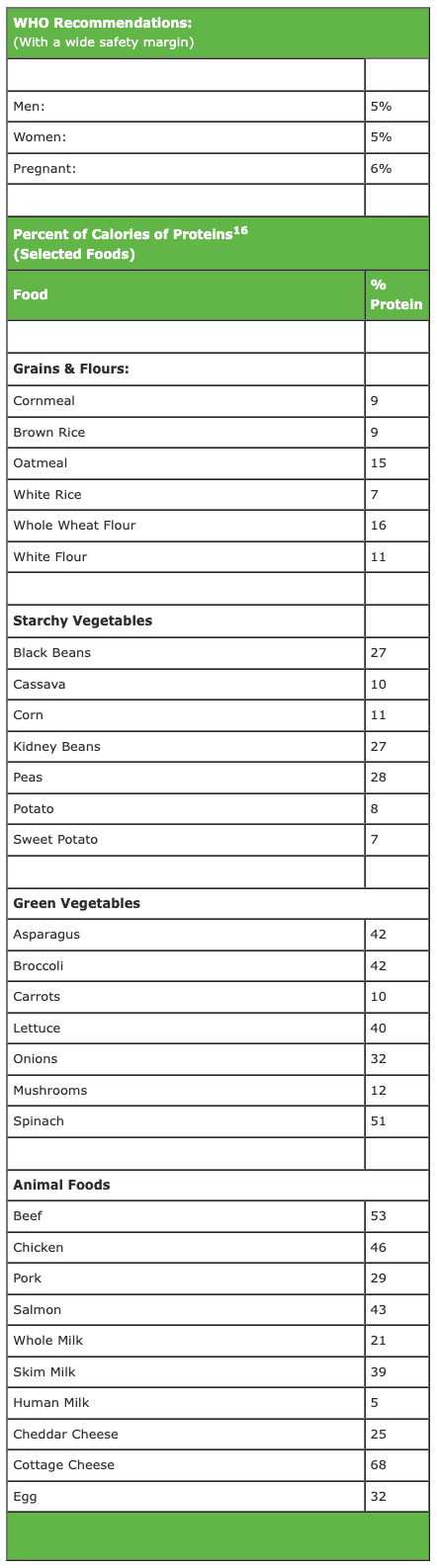

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that men and women obtain 5% of their calories as protein. This would mean 38 grams of protein for a man burning 3000 calories a day and 29 grams for a woman using 2300 calories a day. This quantity of protein is impossible to avoid when daily calorie needs are met by unrefined starches and vegetables. For example, rice alone would provide 71 grams of highly useable protein and white potatoes would provide 64 grams of protein.

Our greatest time of growth‚ thus, the time of our greatest need for protein, is during our first 2 years of life‚ we double in size. At this vigorous developmental stage our ideal food is human milk, which is 5% protein. Compare this need to food choices that should be made as adults‚ when we are not growing. Rice is 8% protein, corn 11%, oatmeal 15%, and beans 27%. Thus protein deficiency is impossible when calorie needs are met by eating unprocessed starches and vegetables.

The healthy active lives of hundreds of millions of people laboring in Asia, Africa, and Central and South America on diets with less than half the amount of protein eaten by Americans and Europeans prove that the popular understanding of our protein needs is seriously flawed.

Faulty Observations Lead to High Protein Recommendations

People commonly believe: the more protein consumed the better. This faulty thinking dates back to the late 1800s, and was established without any real scientific research. An assumption was made that people who could afford to do so would instinctively select a diet containing the right amount of protein. After observing the diets of laborers, soldiers, and workers in Western Europe and the USA, recommendations of 100 and 189 grams of protein a day were established. People’s innate ability to select a proper diet is disproved by the present day popularity of burger joints, donut shops, and pizza parlors.

Further confusion about our protein needs came from studies of the nutritional needs of animals. For example, Mendel and Osborne in 1913 reported rats grew better on animal, than on vegetable, sources of protein. A direct consequence of their studies resulted in meat, eggs, and dairy foods being classified as superior, or “Class A” protein sources and vegetable proteins designated as inferior, or “Class B” proteins. Seems no one considered that rats are not people. One obvious difference in their nutritional needs is rat milk is 11 times more concentrated in protein than is human breast milk. The extra protein supports this animal’s rapid growth to adult size in 5 months; while humans take 17 years to fully mature.

The recent popularity of high protein diets has further popularized the fallacy that “more protein is good for you.” True, high protein diets, like Atkins, will make you sick enough to lose your appetite and temporarily lose weight, but this fact should not be extrapolated to mean high protein is healthy‚ in fact, the opposite is true.

The Truth Has Been Known for More than a Century

In 1903, the head of Yale’s department of biochemistry, Professor Russell Henry Chittenden, reported profound health benefits gained by cutting popular recommendations for protein held at his time by half to two-thirds (from 150 grams to 50 grams daily). His research included detailed dietary histories and laboratory studies of his subjects.

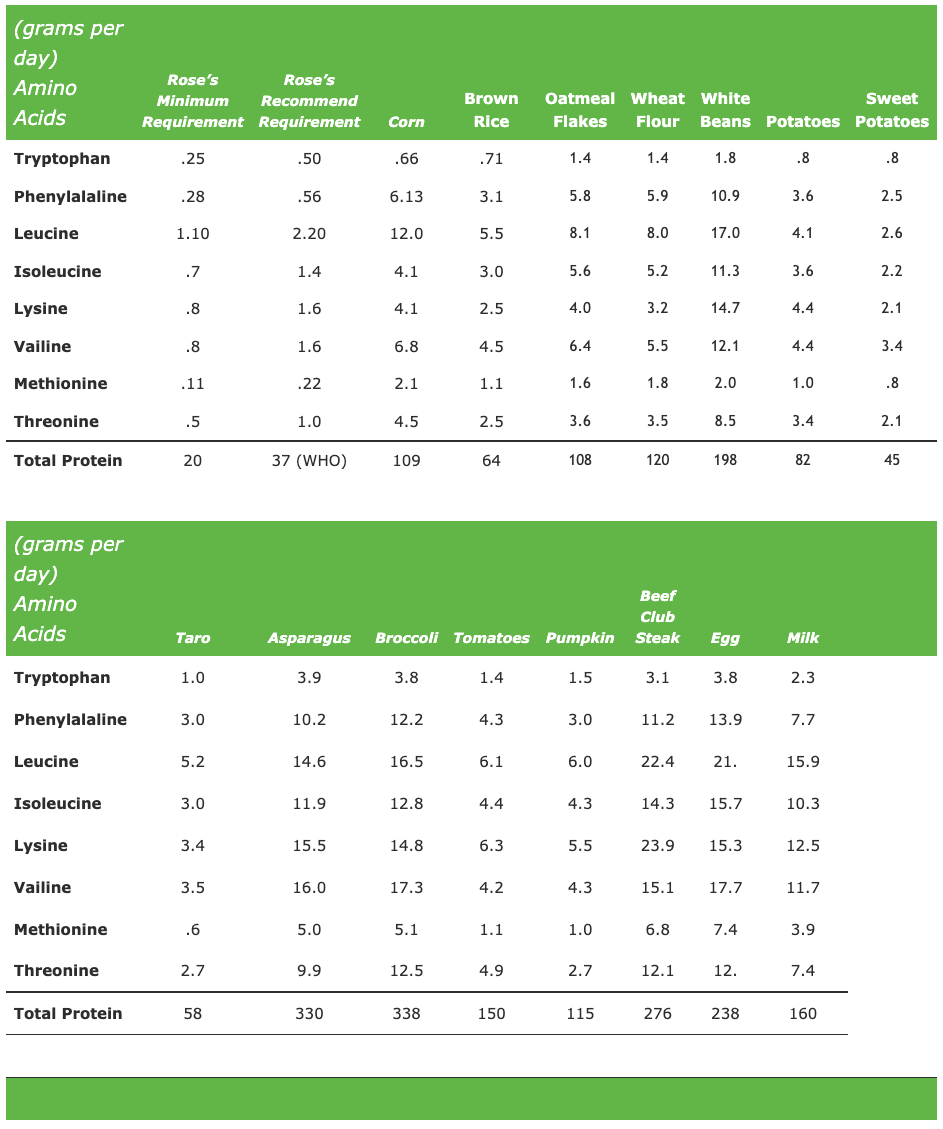

In the 1940s, William Rose performed experiments on people which found daily minimum protein needs to be about 20 grams a day. Further research on men found single plant foods consumed in an amount sufficient to meet daily needs easily met these human requirements for all 8 essential amino acids. (A more detailed discussion of the history of protein recommendations is found in my December 2003 newsletter article: A Brief History of Protein: Passion, Social Bigotry, and Enlightenment.)

The results of Dr. Rose’s studies are summarized in the following chart, under “minimum requirements.” From the chart, it is clear that vegetable foods contain more than enough of all the amino acids essential for humans.

Starving People Die of Fat, Not Protein, Deficiency

In 1981, 10 Irish prisoners from the Republican Army (IRA) went on a hunger strike. Nine out of 10 of these men died between 57 and 73 days (mean of 61.6 days) of starvation after losing about 40% of their body weights (the remaining striker died of complications of a gunshot wound). This experience gave doctors a chance to observe first hand the metabolic changes that occur during starvation. Protein stores were generally protected during starvation, with most of the energy to stay alive being derived from the men’s fat stores. It was estimated that the hunger strikers had lost up to 94% of their body-fat levels, but only 19% of their body-protein levels at the time of death. They died when they ran out of fat. Since fat is more critical than protein, people should be asking, “Where do you get your fat (on any diet)?”

Since Nature designed her plant foods complete, with abundant amounts of fat, protein, carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals, “Where you get a specific nutrient?” is almost never a relevant question, as long as there is enough to eat. So, why have scientists, dietitians, medical doctors, diet-book authors, and the lay public become fixated on a non-existent problem? Protein is synonymous with eating meat, poultry, fish, dairy, and eggs‚ the foods traditionally consumed by the wealthier people in a society‚ thus, protein-eating means higher social status. High-protein foods are also high-profit foods. Therefore, propagating the protein myth is motivated by egos and money‚ and the usual consequences of pain and suffering follow closely behind these two human frailties.

References:

2) Tufts University: Article 1 Article 2

3) Harvard School of Public Health: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/protein.html

4) Northwestern University: http://www.feinberg.northwestern.edu/nutrition/factsheets/protein.html

5) McDougall J. Plant foods have a complete amino acid composition. Circulation. 2002 Jun 25;105(25):e197; author reply e197.

6) McDougall J. Misinformation on plant proteins. Circulation. 2002 Nov 12;106(20):e148; author reply e148.

7) Personal Communication with John McDougall, MD on July 10, 2003.

8) J Pennington. Bowes & Church’s Food Values of Portions Commonly Used. 17th Ed. Lippincott. Philadelphia- New York. 1998.

10) McDougall J. The McDougall Plan. New Win Publ. 1983; pages 95-109.

11) Kon S. XXXV. The value of whole potato in human nutrition. Biochemical J. 1928; 22:258-260

12) Lopez de Romana G. Fasting and postprandial plasma free amino acids of infants and children consuming exclusively potato protein. J Nutr. 1981 Oct;111(10):1766-71.

13) The January 2004 McDougall Newsletter: Protein Overload.

14) The December 2006 McDougall Newsletter: An Inconvenient Truth: We Are Eating Our Planet To Death.

15) Millward DJ. The nutritional value of plant-based diets in relation to human amino acid and protein requirements. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999 May;58(2):249-60.

16) Leiter LA, Marliss EB. Survival during fasting may depend on fat as well as protein stores. JAMA 1982;248:2306

17) ZSurvival. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Sep 1;127(5):405-9.

Recommended Articles

McDougall Moments: Protein and Muscles

Anthony Lim, MD, JD: How to Overcome Stumbling Blocks to Success