Kelly Caraway: Choosing diet over drugs after a heart attack

Joining the Medical Business

One afternoon, in September of 2006, about a month after I turned 58, I was overtaken by excruciating chest pain, nausea, and profuse sweating. I tried to “walk it off” for about two hours at home but finally decided to go to the emergency room. I was sure that if I could just get some pills that everything would be fine. I drove myself 40 miles to the nearest hospital, and the next thing I knew the staff was looking for a helicopter to airlift me to a hospital that treats heart attack victims. I remember thinking, “They must be mistaken, I could never have a heart attack, I’m a healthy man, and I have no history of heart disease or coronary artery disease in my immediate family.” Plus, I thought, heart attacks only happen to other people.

One afternoon, in September of 2006, about a month after I turned 58, I was overtaken by excruciating chest pain, nausea, and profuse sweating. I tried to “walk it off” for about two hours at home but finally decided to go to the emergency room. I was sure that if I could just get some pills that everything would be fine. I drove myself 40 miles to the nearest hospital, and the next thing I knew the staff was looking for a helicopter to airlift me to a hospital that treats heart attack victims. I remember thinking, “They must be mistaken, I could never have a heart attack, I’m a healthy man, and I have no history of heart disease or coronary artery disease in my immediate family.” Plus, I thought, heart attacks only happen to other people.

The doctor said that I had one artery that was completely blocked, which had caused the heart attack, and another artery was significantly blocked. He had opened up the completely blocked artery with a balloon stent, but he did not do anything with the other artery. As a CPA who had worked for a large Texas hospital system for over 37 years, I had always told myself I would never become a patient in a hospital’s progressive care/telemetry unit, but here I was.

That was just the beginning of my education in the differences between how modern medicine treats heart attack victims and how it should treat heart attack victims, in most cases. The medical profession leaves the impression that it is not possible for a heart attack victim to survive without drugs, but it is simply not true. I have learned a lot along my journey, and if at all possible, I hope to spare others from unnecessary surgery and a lifetime of medication.

Working up to My Heart Attack

Having grown up on a farm near San Antonio, Texas, I was a physically active youth. Even as I maintained my sedentary office job as a CPA, I jogged and participated in organized races, including four marathons while in my late 20’s and 30’s. Even into my 40’s and 50’s, after my activity level dropped off somewhat, I was sure that the amount of exercise I was getting was sufficient. I took supplements, never smoked, my total cholesterol ranged from 175mg/dl to 195mg/dl, and my blood pressure and annual physicals were normal, so I generally considered myself to be healthy. Given this, nutrition was of no concern to me. I thought I should be able to eat anything I wanted.

Things began to shift for me in my late 40’s when I was put on an intensive project at work that lasted several months. It often required 12 hours of sedentary work a day and often on the weekends, causing me to halt any type of physical activity. I continued to eat anything and everything, and during this time I gained 25 pounds. I became very sluggish and felt miserable by the end of the project.

When I visited my primary care physician, he told me that I had become a borderline diabetic and he wanted to put me on medication. I asked him to give me some time to see if I could lose weight before I started taking drugs. He reluctantly consented and told me to come back in three months.

This was the first time in my life (my early 50’s) that I started to think about nutrition. I made what I thought were some big dietary changes. My approach to healthy eating was orange juice with a couple of boiled eggs, and either toast and jelly or store-bought waffles and syrup for breakfast. I also ate chicken, lots of “healthy” TV dinners, and salads (but it was more like putting my salad on the oily salad dressing instead of the other way around). By eating this way, along with not sitting in front of a computer as long each day, I was able to lose some of the weight, and my doctor ceased threatening me with diabetic drugs. However, I continued eating sweets and drinking soft drinks, and drank very little water. This was how I was eating when I had my heart attack ….

Apparently Very Confused Heart Doctors

So, as I lay in the telemetry unit, following my heart attack and the insertion of the first stent, the doctor said that he had scheduled me the next day to have a stent inserted into the second artery that he said was significantly blocked. I wondered why he had not done the second artery to begin with; now I was going to have to go through angioplasty again. That made no sense to me, but I did not ask. Later that day I got word that the procedure was cancelled since my insurance would not cover an elective procedure at this hospital. I was given a bunch of prescriptions when I was discharged and was told to make an appointment to have the second stent put in elsewhere.

Two weeks later I arrived at another hospital for my procedure, but at the last minute the doctor had to cancel because of an emergency. It was then suggested that I have a nuclear stress test done in order to determine just how bad the second blockage was. The stress test showed that the blockage was not significant, and the course of action was to watch the blockage to see if I would need to have a stent put in at a later date. If my insurance hadn’t held things up at the first hospital, and if my doctor had been available at the second hospital, I would have been subjected to an unnecessary heart cath procedure. Why wasn’t the nuclear stress test ordered to begin with instead of ordering angioplasty? But again I did not ask. I began to wonder how much I should rely on these doctors.

Poisoned with Good Intentions

A little over a month after my heart attack I was scheduled to see my primary care physician to go over my condition and discuss the medications I was on. He explained that my heart was beating normally and that I would need about six weeks to heal. He also told me I would be on medication for the rest of my life (a beta-blocker, an ace inhibitor, Zocor—a statin for cholesterol, and an aspirin).

After this visit I started to embark on my own research. Purely by accident I ran across Dr. John McDougall’s website and an article about avoiding heart bypass surgery and angioplasty by changing one’s diet. I was impressed that he offered scientific proof and personal experience to support what he was saying about the benefits of a plant-based diet. Hearing about the experiences of others on his website was also extremely helpful. I found that not only was there hope, but I could actually be responsible for my own destiny through changing the way I ate.

About six weeks after my heart attack I switched to a plant-based diet and cut out soft drinks, fruit drinks, and sweets. After being on the plant-based diet, along with my medication, for about six weeks, my total cholesterol dropped from 195mg/dl to 80mg/dl, my LDL went down to 25mg/dl, and my triglycerides came down to 150mg/dl. But I kept on taking all my medications.

It was about this time that I started having some unusual symptoms that I thought might be caused by my heart attack. I was trying to walk as much as I could but felt really sluggish. Every time I bent over and straightened up I would almost pass out. The muscles in my legs would ache and hurt so much that I could hardly stand it at times. My blood pressure was being forced down with drugs to a top number lower than 110 and the bottom reading to less than 70. As I researched the drugs I was taking, I found that they were most likely the cause of my symptoms. When I consulted the cardiologist about my symptoms and asked him about eliminating or lowering the dosages of some of my drugs, he absolutely refused. After almost begging him to at least lower the cholesterol drug (Zocor) he finally consented to reduce it from 40mg to 20mg. This provided absolutely no relief.

After having more blood work done (another six weeks later), my total cholesterol actually went down even more to 79mg/dl and my LDL was at 26mg/dl (even after I had reduced the strength of the Zocor). My primary care physician, just like the cardiologist, did not want to lower or eliminate any of the drugs I was taking, even though it seemed that my plant-based diet (without a cholesterol drug) was more than sufficient to manage my cholesterol.

Taking Self-control

After five months of taking drugs I gradually started reducing some of them on my own to see if they were causing the symptoms. I first eliminated the Zocor, and three months after I had completely eliminated it I had more blood work done. My total cholesterol, just from the plant-based diet and my exercise program, was 105mg/dl, and my LDL was 52mg/dl, both very positive numbers (compared to my total cholesterol of 195mg/dl and LDL of 92mg/dl before my heart attack). For the first time since I had started taking the drugs, the pain and aching in my legs disappeared, and now, 11 months after my heart attack, I am off the other drugs (I still take the aspirin but have reduced it to 81mg instead of the 325mg that the doctors insisted I should take).

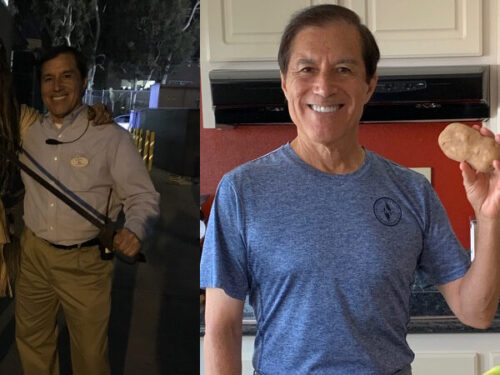

I feel fine now that I am just on the plant-based diet along with the baby aspirin and my exercise program. My blood pressure is normal, my total cholesterol remains well under 150mg/dl, my LDL remains under 70mg/dl, my triglycerides remain under 150mg/dl, my glucose level remains under 100mg/dl and I am able to run/walk seven miles a day with no side effects. My weight is down 15 pounds since my heart attack to a level that is considered normal. My heart rate is also significantly lower than what it was before I had the heart attack. In addition, I have noticed remarkable improvement in my sleep since I have been on the plant-based diet.

Even though my primary care physician insisted that I should be taking the standard drug regimen for heart attack survivors, he now admits that the plant-based diet may provide some real health benefits, such as healing my arteries. He says that he does not have any knowledge of any studies that have been done on heart attack survivors who are just on a plant-based diet alone (without the standard medications that are normally prescribed to heart attack survivors). As far as the cardiologists; they are concerned and still feel the standard drug treatment is the only way to go. As for me, I fully expect to remain on a plant-based diet the rest of my life.

Kelly Caraway

San Antonio, Texas

Dr. McDougall’s Comments

When I meet patients with coronary artery (heart) disease, without even asking, I know what medications they are taking: a statin, beta-blocker, ace inhibitor, aspirin and Plavix. If they have had chest pain then their recent history includes an angiogram, angioplasty with stent, and/or a bypass operation. Essentially all doctors practice with such little original thought that it would appear as if they are reading from a cookbook. This absolute uniformity of prescriptions might be warranted if the results were as perfect as grandma’s Thanksgiving dinner. But, they are not, and the prescribing doctors know this all too well. They know that 8 out of 8 studies performed to establish the benefits of angioplasty with or without stents all show no improvement in survival. Every well-read doctor knows that bypass surgery does not save lives in the vast majority of cases, and that all patients attached to the heart-lung machine during this major operation suffer from brain damage, at least to some degree. Anyone interested in reading scientific research quickly concludes that the absolute benefits from the pile of pills patients are asked to swallow daily are far less than those professed by their doctors; with troublesome side effects glossed over by these same professionals.

You might ask, “How can such a charade continue?” Don’t act surprised when I say “cash rules.” Look at your own business. Doesn’t the profit margin steer every decision? Why should the medical businesses be any different? Naïve thinking leads people to conclude that doctors, drug companies, and hospitals work with a higher level of ethics than everyone else because the consequences of their efforts are people’s lives—my wife, my husband, my child are at stake. So what!

In fact, the medical businesses are more loathsome because they operate with undeserved respect. We place doctors on a pedestal of honesty and trust only deserved by most of our parents. When I was growing up I knew that my mother and father always acted in my best interest—they loved me so much no amount of money counted more. We have transferred childhood feelings about our parents to our doctors—with this mistake, we pay with our money and our lives.

Doctors should not ask for, nor should they expect to receive, such blind faith from consumers, because when these professionals fail to deliver perfection—a perfect baby, a perfect operation, or an absolute cure—we become more than disappointed. We feel we have been failed by someone who figuratively stands next to God. A commonplace reaction is to seek revenge for such a grand disillusionment—a lawsuit.

Kelly Caraway is one of the growing numbers of patients asking himself hard questions about the doctor and drug businesses. Access to information once buried in libraries, and purposefully concealed from consumers by industries, is now available through the Internet. Not only can average people defend themselves against harmful treatments, but they can also take the monumental step of learning how to heal themselves through a sensible, profit-free, diet and exercise program.

Learn more about Heart Disease & Atherosclerosis.

Recommended Articles

Lyndall Shick: Had Her First Heart Attack at 41

Al: Got off Statins, Healed GERD and Returned to his College Weight!