Common Health Problems: Kidney Disease (Kidney Failure, Nephritis)

There are many causes of kidney damage. You must pay attention to those you can control. Fats and cholesterol in the diet promote atherosclerosis in the kidney arteries, which is one of the leading causes for failing kidneys. Add to this diabetes or high blood pressure and you invite almost certain kidney trouble by eating too well, but not at all wisely.

Among the most subtle and important of the many toxic threats to the kidneys are the excess amounts of proteins that are consumed by the average person who eats our rich American foods. The daily intake of more proteins than the body really needs means that the excess must be eliminated through the kidneys. We’re equipped with no storage depots for proteins, as we are for fats.

The proteins not used for body repair and growth float around in the blood stream until they are metabolized by the liver and their remnants are removed by the kidneys. The filtering units in the kidneys are called nephrons. Destruction of these nephrons occurs directly from exposure to those proteins or to the products of their degradation. The damage from excessive intake of proteins is so common that, in an otherwise healthy person, 25-50% of the functional capacity of the kidneys will be destroyed after eight decades of high living American-style. Even so, we’re lucky to have much reserve tissue to rely on: with only 25% of kidney function remaining, plenty of tissue cells still survive to handle the waste products of body metabolism, and the damaged and failing kidneys go unnoticed. Our bodies are very forgiving!

But not forever. This damaging effect from a high protein diet becomes a life and death matter with someone who has already lost kidney tissue from one or more other causes. For example, a person with diabetes, high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, physical injury, or surgical loss will be under a great disadvantage. Unfortunately, serious instruction about the value of a low protein diet is an important part of essential education that is missing from the medical care given most patients who have lost part of their kidney function.

Glomerulonephritis

Twelve children (aged 4-16) were studied, who suffered from nephrotic syndrome due to glomerulonephritis (the condition where the kidneys become inflamed, pass large amounts of proteins and blood into the urine, while the body’s tissues swell with accumulating fluid). All of the children had failed to respond to treatment with powerful anti-inflammatory drugs called steroids, and many also failed on anti-cancer drugs called cyclophosphamides. During the study, they were started on a diet that excluded common causes of food allergies – dairy products, eggs, pork products, tomatoes, etc. In four of the children the nephrotic syndrome improved in less than a month. Within 4 to 6 months remission was seen in six children. Then three were challenged with a dairy product, milk, and all three had an immediate recurrence of glomerulonephritis.

Thus a debilitating, often fatal, kidney disease, was cured in half the patients by simply excluding from their diets some common causes of food allergies, especially dairy products. Apparently the proteins in milk (or in other foods) succeed in entering the body through the walls of the intestinal tract. Once in the blood stream, these proteins are attacked by antibodies (proteins synthesized by our own immune system in order to attack foreign invaders) such as bacteria, viruses, and food proteins. The milk proteins and antibodies form complexes that are filtered out of the circulating blood in the small capillaries of the kidneys.

Once stuck in the kidney tissues, these complexes act like a sliver of wood stuck in the skin–causing inflammation. The inflamed cells in the kidneys leak blood and protein into the urine. Soon the injured kidney tissues are permanently damaged, and the kidneys begin to fail. Many other investigators have reported the “cure” of nephrotic syndrome by the elimination of milk and other animal proteins, such as pork. Presumedly, the cause of the condition is present in the foodstuffs that were eliminated.

Current Treatment: People with kidney disease often lose proteins in their urine, and because of this some doctors mistakenly recommend a high protein diet in an attempt to compensate for the loss. The effort is foolish. All natural diets, whether based on plants or on animal foods, provide plenty of proteins. The strategy of adding even more protein in the diet not only does not help to affect the body’s protein balance, but actually worsens the kidney disease.

The best treatment for someone having kidney trouble is a low protein, low fats, low sodium, low phosphates, and cholesterol-free diet. Potassium (high in fruits and vegetables) needs to be limited as the kidney disease progresses. Someone with a serious degree of the disease should unquestionably be under the care of a competent specialist.

Recommendations

+-Try to identify the spiral cause of the condition, such as the specific animal protein that is responsible for many cases of glomerulonephritis. Eliminate these damaging meats and dairy products from all meals, thereby protecting and preserving the kidney functions that remain.

To begin with, in order to prevent development of any kidney destruction at all, follow a low-fat, low-cholesterol, diet with limited and reasonable amounts of proteins. If damage has already occurred, then the amount of proteins must be restricted much further. To lower the protein intake while on a starch-based diet, consumptions of beans, peas and lentils must be restricted even more (indeed, often eliminated entirely). If failure is far advanced, then simple sugars, even refined white sugar, should be added to your diet in order to increase the number of calories without relying upon more proteins. The goal is about 20-30 grams of proteins a day. (Consider that a diet of white rice alone (2000 to 3000 calories) provides 40 to 60 grams of proteins a day.)

Medications may be needed to control symptoms of kidney failure. Kidney dialysis may be your last resort, short of a kidney transplant. (See Kidney Disease in McDougall’s Medicine-A Challenging Second Opinion for further details.

References

+-Genova, R. Food allergy in steroid-resistent nephrotic syndrome (letter). Lancet 1:1315, 1987

Lagrue, G. Food sensitivity and idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (letter). Lancet 2:777, 1985

Lagrue, G. Food sensitivity in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (letter). Lancet 2:777, 1987

Howanietz, H. Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome, treated with steroids for five years, found to be allergic reaction to pork (letter), Lancet 2:450, 1985

Sato, M. Estimation of circulating immune complexes following oral challenges with cow’s milk in patients in IgA nephropathy. Nephron. 47:43, 1987

Russell, M. IgA-associated renal disease: antibodies to environmental antigens in sera and deposition of immunoglobins and antigens in glomeruli. J. Clin. Immunol. 6:74, 1986

Brenner, B. Dietary protein intake and the progressive nature of kidney disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 307:652, 1982

Bay, W. The living donor in kidney transplantation. Ann. Intern. Med. 106:719,1987

Giovannetti, S. Answers to ten questions on the dietary treatment of chronic renal failure. Lancet 2:1140, 1986

Evanoff, G. Prolonged dietary protein restriction in diabetic nephropathy. Arch. Intern. Med. 149:1129, 1989

Recommended Articles

Common Health Problems: Fatigue

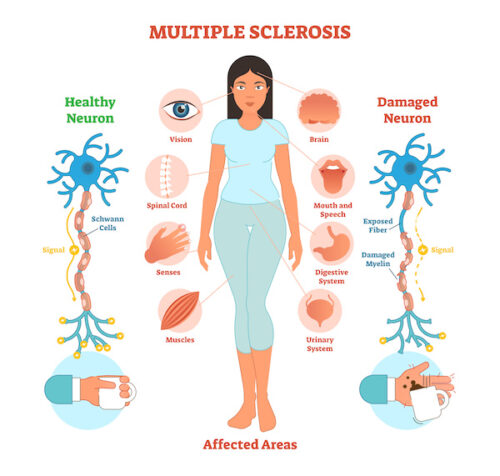

Common Health Problems: Multiple Sclerosis (MS) & Diet