|

A Brief History of

Protein: Passion, Social Bigotry, Rats, and Enlightenment

Nutrition

is an emotional subject and nothing arouses people�s passions more than

the subject of protein in their diet. Widely divergent opinions on

whether more protein or less is best, and on the merits of animal vs.

vegetable sources, have been debated for more than 150 years. And for all

that time solid scientific research has clearly supported the

wisdom of a diet low in protein � favoring vegetable sources. So far,

however, the scientific facts have fought a losing battle against

popular opinion � which values high-protein diets based on animal

foods. Mark Twain once said, �Truth is mighty and will prevail. There is

nothing wrong with this, except that it ain't so.� Even though the facts

may never become popular knowledge, I will always believe it is your

fundamental right to know the truth about your nutritional requirements �

this vital information should be taught from childhood as basic education,

along with reading, writing, and mathematics � and along with health facts

such as cigarettes cause lung damage, drunk driving kills, and automobile

safety belts save lives.

High Protein

Standard Set by Social Bigotry

One of the earliest

proponents of high protein diets was the distinguished German physiologist

Dr. Carl Voit (1831-1908).1,2 After studying laborers who

consumed approximately 3100 Calories daily, he concluded that protein

intake for people should be 118 grams (g) per day � this value became

known as the �Voit standard.� How did he reach this conclusion? He

believed that people with sufficient income to afford almost any choice of

foods � from meat to vegetables � would instinctively select a diet

containing the right amount of protein to maintain health and

productivity. Other European and American authorities made similar

observations about the eating habits of working men with sufficient

incomes to afford meat and came to similar conclusions � ultimately

recommending diets high in protein (100 and 189 grams of protein a day).

No experiments were performed on the human body to reach these

conclusions. Information on the diets of vigorous individuals living

during these times and following low-protein vegetarian diets was largely

ignored.2,3 The healthy active lives of hundreds of millions

of less affluent people laboring in Asia, Africa, and Central and South

America on diets with less than half the amount of protein recommended by

Dr. Voit (and almost no meat), were overlooked when experts established

protein requirements that still affect us today.3,4

What arrogance! To

conclude that the superior intellect of moderately affluent people of

European descent would cause them to naturally come to correct conclusions

about their personal nutritional needs. What foolishness! You can see the

effects of self-selection when unrestricted food choices are available.

What do more than one billion people living in the 21st century

choose? McDonald�s, Burger King, Pizza Hut � need more be said about

people�s innate wisdom to make food selections in their best interests?

Unfortunately, these flawed recommendations based upon such social

bigotry have not yet been silenced by over 100 years of scientific

research.

Russell Henry

Chittenden Tells the Truth a Century Ago

Such narrow-minded

thinking should have been stopped by 1905 when Russell Henry Chittenden,

Yale University

Professor of Physiological Chemistry, published his

scientific findings on human protein needs in his classic book,

Physiological Economy in Nutrition.2 Professor

Chittenden believed Dr. Voit had cause and effect reversed: people did not

become prosperous because they ate high protein diets, but rather they ate

meat and other expensive high protein foods because they could afford

them. One hundred years ago he wrote, �We are all creatures of habit,

and our palates are pleasantly excited by the rich animal foods with their

high content of proteid (protein), and we may well question whether our

dietetic habits are not based more upon the dictates of our palates than

upon scientific reasoning or true physiological needs.� Professor of Physiological Chemistry, published his

scientific findings on human protein needs in his classic book,

Physiological Economy in Nutrition.2 Professor

Chittenden believed Dr. Voit had cause and effect reversed: people did not

become prosperous because they ate high protein diets, but rather they ate

meat and other expensive high protein foods because they could afford

them. One hundred years ago he wrote, �We are all creatures of habit,

and our palates are pleasantly excited by the rich animal foods with their

high content of proteid (protein), and we may well question whether our

dietetic habits are not based more upon the dictates of our palates than

upon scientific reasoning or true physiological needs.�

He reasoned that we

should know the minimal protein requirement for the healthy man (and

woman), and believed that any protein intake beyond our requirements could

cause injury to our body, especially to the liver and kidneys. As he

explained it, �Fats and carbohydrates when oxidized in the body are

ultimately burned to simple gaseous products�easily and quickly

eliminated...� �With proteid (protein) foods�when oxidized, (they) yield

a row of crystalline nitrogenous products which ultimately pass out of the

body through the kidneys. (These nitrogen-based protein byproducts) �

frequently spoken of as toxins � float about through the body and may

exercise more or less of a deleterious influence upon the system, or,

being temporarily deposited, may exert some specific or local influence

that calls for their speedy removal.� With these few words Professor

Chittenden explained the deleterious effects of diets high in protein and

meat � consequences too few practicing doctors know about today.

The First

Scientific Experiments on Our Protein Needs

Professor Chittenden�s

first experiment was on himself. For nine months, he recorded his own

body weight, which decreased from 143 pounds (65 Kg) to 128 pounds (58 kg)

on his new diet of one-third the protein that Dr. Voit recommended.

Chittenden's health remained excellent and he described his condition as

being with �greater freedom from fatigue and muscular soreness than in

previous years of a fuller dietary.� He had suffered from arthritis of

his knee and discovered that by reducing his intake of meat his condition

disappeared and his �sick headaches� and bilious attacks (abdominal pains)

no longer appeared periodically as before; plus he fully maintained his

mental and physical activity, with a protein intake of about 40 grams a

day.

Chittenden performed

valid scientific studies by collecting data on the daily dietary and urine

histories of his subjects (including himself) to determine protein

utilization. Because he was contradicting the known �truths� of his time,

he proceeded with extreme caution with his further investigations. He

organized three controlled trials with increasing demands for testing the

adequacy of diets lower in protein than commonly recommended.

The first trial

involved a group of five men connected with Yale University, leading

active lives but not engaged in very muscular work. On a low-protein diet

(62 grams daily) for 6 months, they all remained healthy and in positive

nitrogen balance (more protein went into, than out of, their bodies). The

second trial used 13 male volunteers from the Hospital Corps of the U.S.

army. They were described as doing moderate work with one day of vigorous

activity at the gymnasium. They remained in good health on 61 grams of

protein daily. His final trial was with 8 Yale student athletes, some of

them with exceptional records of athletic events. They ate an average of

64 grams of protein daily while maintaining their athletic endeavors, and

improving their performance by a striking 35 percent. Following these

studies, Chittenden in 1904 concluded that 35�50 g of protein a day was

adequate for adults, and individuals could maintain their health and

fitness on this amount. Studies over the past century have consistently

confirmed Professor Chittenden�s findings, yet you would hardly know it

with the present day popularity of high protein diets.

Rats Confuse

Nutritionists

Many people have the

idea that animal foods contain protein which is superior in quality to the

protein found in plants. This misconception dates back to l9l4, when

Lafayette B. Mendel and Thomas B. Osborne studied the protein requirements

of laboratory rats and demonstrated nutritional requirements

for the individual amino acids.5 They found that rats grew

better on animal sources of protein than on vegetable sources. So,

investigators at that time suspected that the vegetable foods had

insufficient amounts of some of the amino acids essential for the normal

growth of rats. Because of these and other animal-based experiments,

flesh, eggs, and dairy foods were classified as superior, or "Class

A" protein sources. Vegetable proteins were designated inferior,

or "Class B" proteins.

Studies completed in

the early 1940's by Dr. William Rose of the University of Illinois found

that l0 amino acids were

essential for a rat�s diet.6 The

removal of any one of these essential amino acids from the food of growing

rats led to profound nutritive failure, accompanied by a rapid decline in

weight, loss of appetite, and eventually death. Animal products, such as

meat, poultry, milk, and eggs prevented this decline in the rats� health,

and were found to contain the l0 essential amino acids in just the right

proportions for needs of growing rats. Based on these early rat

experiments the amino acid pattern found in animal products was declared

to be the �gold standard� by which to compare the amino acid pattern of

vegetable foods. According to this concept, wheat and rice were declared

deficient in lysine and corn was deficient in tryptophan. essential for a rat�s diet.6 The

removal of any one of these essential amino acids from the food of growing

rats led to profound nutritive failure, accompanied by a rapid decline in

weight, loss of appetite, and eventually death. Animal products, such as

meat, poultry, milk, and eggs prevented this decline in the rats� health,

and were found to contain the l0 essential amino acids in just the right

proportions for needs of growing rats. Based on these early rat

experiments the amino acid pattern found in animal products was declared

to be the �gold standard� by which to compare the amino acid pattern of

vegetable foods. According to this concept, wheat and rice were declared

deficient in lysine and corn was deficient in tryptophan.

Subsequent research

has shown the obvious: the initial premise, that animal products supply

the most ideal protein pattern for humans, as they do for rats, is

incorrect.7 The dietary needs of rats are considerably

different from those of humans, mainly because rats grow very rapidly into

adult size as compared to people. Rats are fully adult after 6 months;

whereas a person takes 17 years to fully mature. This difference in need

is especially clear when the breast milk of both species is examined and

compared. The protein content of rat breast milk is 10 times greater than

the milk intended for human babies.8,9 Baby rats double in

size in 4.5 days; an infant doubles in size in 6 months. The obvious

reason for the different needs is because rats grow very rapidly into

adult size as compared to humans; therefore requirements for protein to

support that growth are very much higher.

Dr. William Rose

Discovers Human Needs

In 1942, Dr. William

Rose turned his attention from rats to people and began studying the amino

acid requirements for humans using basically the same methodology

he had used with rats. Healthy, male graduate students, grateful in

those days for the free food, the dollar a day they were paid

and the prospect of getting their initials in print in Rose's

widely read publications, served as his experimental

animals. They were fed a diet consisting of corn starch,

sucrose, butter fat without protein, corn oil, inorganic salts,

the known vitamins, and mixtures of highly purified amino

acids. Their diet also included a large brown "candy," which

contained a concentrated liver extract to supply unknown vitamins,

sugar, and peppermint oil to provide a "never-to-be-forgotten

taste."

The study used a

chemical measurement called nitrogen balance to determine whether

the subjects were getting enough usable protein from the mixture. From

his experiments, Dr. Rose found that only eight of the ten amino acids

essential to rats were also essential to men � we were better at making

two amino acids than rats. When an essential amino acid was given in

insufficient amounts for approximately two days, all subjects complained

bitterly of similar symptoms: a clear increase in nervous irritability,

extreme fatigue, and a profound failure of appetite. The subjects were

unable to continue the amino acid deficient diets for more than a few days

at a time.

Through his studies,

Dr. Rose also determined a minimum level of intake for each of the eight

essential amino acids.10 He found small amounts of variation in

individual needs among his subjects. Because of these unexplained

differences among people, he included a large margin of safety in his

final conclusion on minimum amino acid requirements. For each amino acid,

he took the highest recorded level of need in any subject, and then

doubled that amount for a "recommended requirement" � described as a

definitely safe intake. It is important to realize that his higher

requirement is easily met by a diet centered around any single starchy

vegetable. Even in children, as long as energy needs are satisfied by

starch, protein needs are automatically satisfied in almost every

situation because of the basic and complete design of the food. These

investigations were completed by the spring of 1952, resulting in sixteen

papers in The Journal of Biological Chemistry that are considered

classic contributions in the history of nutrition for the benefit of human

beings.

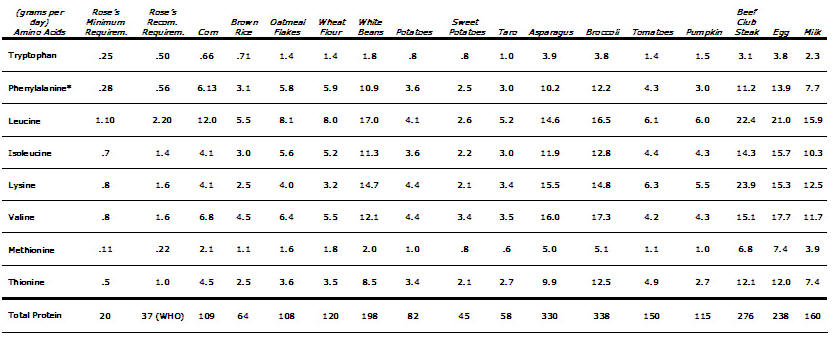

The results of Dr.

Rose`s studies are summarized in the following chart, under "minimum

requirements". From the chart, it is clear that vegetable foods contain

more than enough of all the amino acids essential for humans.11

Many investigators

have measured the capacity of plant foods to meet our protein needs.

Their findings show that children and adults thrive on diets based on a

single starch; and they grow healthy and strong.11,12

Furthermore, no improvement is obtained by mixing plant foods or

supplementing with amino acid mixtures to make the combined amino acid

pattern look more like that of flesh, dairy, or eggs.12 (For a

thorough discussion of human protein needs see The McDougall Plan,

New Win Publishers.)

Diet for a Small Planet Helps and Harms

A popular book among

vegetarians, Diet for a Small Planet, by Frances Moore Lappe�

published in 1971, started a revolution that has had a positive impact for

the past three decades on the lives of millions of people. Unfortunately,

Ms. Lappe� failed to understand the basic scientific literature on human

protein needs and the sufficiency of plants foods before she wrote her

influential book. She believed plants contained �incomplete proteins�

with insufficient amounts of certain essential amino acids to meet the

needs of people.13 As a result of this misunderstanding, she

placed great emphasis on combining vegetable foods to create an amino acid

pattern which resembles that found in animal foods. This emphasis is

unnecessary and implies that it is difficult to obtain �complete� protein

from vegetables without detailed nutritional knowledge. Because of her

complicated and incorrect ideas people are frightened away from

vegetable-based diets.

The impact of her

incorrect teachings of more than 30 years ago affects nutritional policy

even today. In 2001 the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart

Association published a long overdue review warning people of the dangers

of high protein diets, like the Atkins, the Zone, and Sugar Busters diets.14

Unfortunately, this one statement in an otherwise valuable report is

scientifically incorrect: �Although plant proteins form a large part of

the human diet, most are deficient in 1 or more essential amino acids and

are therefore regarded as incomplete proteins.� For a supporting

scientific reference the Committee cites Frances Moore Lappe�s 1971 book,

Diet for a Small Planet.

You may think this is

a trivial matter; however, incorrect information on our protein needs can

have grave consequences on your health and your family�s health. With the

American Heart Association teaching that plants fail to supply complete

protein you are almost certain to receive incorrect, potentially damaging,

medical advice. For example, say you go to your doctor after a heart

attack and mention that you are now going to become a pure vegetarian to

avoid future heart trouble. Your doctor may respond, �You can�t do that,

you will become protein deficient on an all plant food diet � the Heart

Association says so.� Or your child is sick with recurrent asthma and ear

infections and you want a dietary cure � you may be warned away from a

highly effective therapy because members of the Nutrition Committee of the

American Heart Association fail to understand basic scientific research

about human protein needs and plant foods. So this is no small matter.

I have confronted the

Heart Association about spreading misinformation that can result in

suffering as serious as death from heart disease � so far they have shown

no interest in making overdue corrections to their incorrect teaching.

(See my July, August and November 2002 Newsletters for more information

on this.) I recently shared my conflict with the Heart Association with

the world�s leading authority on human protein requirements, Dr. D. Joe

Millward from the Center for Nutrition and Food Safety, School of

Biological Sciences University of Surrey, UK. His response to me on July

10, 2003 was, �Contrary to general opinion, the distinction between

dietary protein sources in terms of the nutritional superiority of animal

over plant proteins is much more difficult to demonstrate and less

relevant in human nutrition. This is quite distinct from the AHA position

which in my view is wrong.� 15

So How Do You Know the Truth about Your Protein Needs?

Read the scientific

literature (www.nlm.nih.gov)

and look at the world picture. Notice that 60 percent of people alive

today and most of the people who have lived in the past have obtained

their protein from plant foods. They have lived successfully; avoiding

all the diseases common in our society. Even today plant sources provide

65% of the world supply of the protein we eat.

What about the

starving children in Africa? The picture one often sees of �protein

deficient� children in famine areas of Asia or Africa is actually one of

starvation and is more accurately described as �calorie deficiency.�11

When these children come under medical supervision, they are nourished

back to health with their local diets of corn, wheat, rice, and/or beans.

Children recovering from starvation grow up to l8 times faster than usual

and require a higher protein content to provide for their catch-up in

development � and plant foods easily provide this extra amount of

protein. Even very-low protein starchy root crops, such as casava root,

are sufficient enough in nutrients, including protein, to keep people

healthy.3

The World Health

Organization knows the truth. Since 1974 it has recommended that adults

consume a diet with 5% of the calories from protein � this would mean 38

grams of protein for a man burning 3000 calories a day and 29 grams for a

woman using 2300 calories a day. These minimum requirements provide for a

large margin of safety that easily covers people who theoretically could

have greater protein needs � such as accident victims or people with

infections. This quantity of protein is almost impossible to avoid if

enough whole plant food is consumed to meet daily calorie needs. For

example, rice alone would provide 71 grams of highly useable protein and

white potatoes would provide 64 grams of protein for a working man.16

For a pregnant woman the WHO recommends 6% of the calories come from

protein � again an amount of protein easily provided by a diet based on

starches, vegetables, and fruits.

Human Breast Milk � Your Final Assurance

Your greatest need for

protein is when you grow the most. The greatest time of growth in a human

being�s life is as an infant. We double in size during the first 6

months. The ideal food for a baby is mother�s milk. Therefore, breast

milk is the �gold standard� for nutrition � during your time of greatest

need for all nutrients, including protein. Five to 6.3 percent of the

calories in human breast milk are from protein.9,17 This is

the maximum concentration of protein we will ever need in our food

supply. Knowing this value tells us that at no other time in our life

will we ever require more protein. Consider the protein content of the

foods we consume after weaning � these are even higher in protein � rice

is 9%, potatoes are 8%, corn is 11% and oatmeal is 15% protein.16

Wrong Thinking

Ruins Health

Even though all the

scientific knowledge accumulated over the past 100 years clearly shows our

bodies were designed to live best on a diet lower in protein than dictated

by common belief, we continue on the same disastrous dietary path. As

Russell Henry Chittenden explained 100 years ago, �The poorer man emulates

his richer neighbors as soon as his circumstances permit, and resources

that could be much more advantageously expended for the good of the family

and the home are practically wasted � to say nothing of possible injury to

health � under the mistaken idea that this more generous method of living

(a high-protein, high-meat diet) is the surest road to health and

strength.�2 Dr. Chittenden also believed that knowledge and

the truth would prevail. He wrote, �Habit and sentiment play such a part

in our lives that it is too much to expect any sudden change in custom.

By a proper education commenced early in life it may, however, be possible

to establish new standards, which in time may prevail and eventually lead

to more enlightened methods of living...� The past century of declining

health for people living in developed countries has proved Chittenden

wrong � so far. However, with widespread communication via the Internet

his predictions may soon become reality.

References:

1) Carpenter K. A

short history of nutritional science: part 2 (1885-1912). J Nutr.

2003 Apr;133(4):975-84.

2) Chittenden, R. H.

(1904). Physiological economy in nutrition, with special reference to the

minimal protein requirement of the healthy man. An experimental study. New

York: Frederick A. Stokes Company.

3) Millward DJ.

The nutritional value of plant-based diets in relation to

human amino acid and protein requirements. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999

May;58(2):249-60.

4) Millward DJ.

Metabolic demands for amino acids and the human dietary

requirement: Millward and Rivers (1988) revisited. J Nutr. 1998

Dec;128(12 Suppl):2563S-2576S.

5) Osborne T.

Amino-acids in nutrition and growth. J Bio Chem. 1914; 17:325-49.

6) Rose W.

Comparative growth of diet containing ten and nineteen amino acids, with

further observation upon the role of glutamic and aspartic acid. J Bio

Chem. 1948; 176: 753-62.

7) Bicker M. The

protein requirement of adult rats in terms of the protein contained in

egg, milk, and soy flour. J Nutr 1947;34: 491.

8) Bell G.

Textbook of Physiology and Biochemestry, 4th ed., Williams and

Wilkins, Baltimore, 1959, p. 12.

9) Reeds PJ.

Protein nutrition of the neonate. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000

Feb;59(1):87-97.

10)

Rose W. The amino acid requirement of adult man.

Nutr Abst Rev. 1957;27:63l-47.

11) McDougall J.

(1983). The McDougall Plan.

Clinton, NJ. New Win

Publishing.

12) M. Irwin, Hegsted

D. A conspectus of research on protein requirements of man. J Nutr.

1971;101:385-428.

13) Moyer G. Frances

Moore Lappe�s new edition says it all. Nutrition Action, Oct. 1982. p.

10-11.

14) St. Jeor S,

Howard B, Prewitt E. Dietary protein and weight reduction. A statement

for health professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the Council on

Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism of the American Heart

Association. Circulation 2001;104:1869-74.

15) Personal Communication with John McDougall, MD on

July 10, 2003.

16) J Pennington.

Bowes & Church�s Food Values of Portions Commonly Used. 17th

Ed. Lippincott. Philadelphia- New York. 1998.

17) Reeds PJ.

Protein and amino acid requirements and the composition of complementary

foods. J Nutr. 2003 Sep;133(9):2953S-61S.

|